Walk 12 - A Walk Around the Roman London Wall

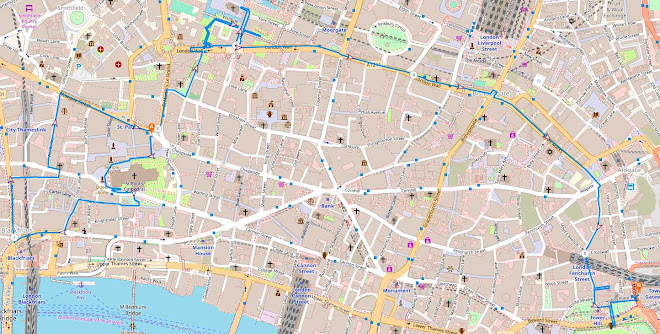

Approximately 3.5 Miles / 5.5 Km

(allow 2.5 hours)

Click here if you wish to see an on-line zoomable version of the map

WALK OVERVIEW

Among other things, on this walk you will:

- Walk the complete path of the Roman and Medieval London Wall, from Blackfriars to the Tower of London

- See how the London Wall is reflected in the landscape and street names of the City

- Find numerous remains of the London Wall preserved around the City

- Find where the Roman Fort on which the Wall was built was

INTRODUCTION TO THE LONDON WALL

The Romans had invaded Britain in the mid first century. They built a square London Fort in around 110 CE, to the north west of what became Londinium. It is thought that the Fort housed around 1,000 troops.

The main part of the London Wall was built by the Romans in approximately 200 CE, around the Roman town of Londinium, and incorporating the Fort.

It’s argued that the reason for the London Wall being built, was either a defensive barrier against the Celtic Tribes, or a way that Albinus, the governor of Britain at the time, could protect the city from Septimius Severus, a Roman rival that he was in conflict with. Others suggest that it was built to help control (and tax) the flow of goods.

The Romans left Britain in about 410 CE.

The Fort, the Wall and the Gates

The Anglo Saxons may have used the abandoned city for a time, but then withdrew and moved further upstream on the Thames, settling around the area where the Strand is now. Later still, perhaps as a result of conflict with the Vikings, they moved back into the walled city, as it afforded more protection.

In the later Middle Ages, population rises meant that settlements spread outside of the London city walls. The Wall was still an important part of London, and was rebuilt and improved for defence and controlling the flow of the population. This continued through the time of the Wars of the Roses, and to beyond the Tudor period.

As the population of London grew and traffic increased, the wall and the narrow gates became a problem. From around the 18th century onward, large parts of the wall and the city gates were demolished, or made part of other buildings. See this post in the excellent Spitalfieldslife.com to see what the gates looked like before they were demolished.

This walk follows, as near as possible, where the Roman London Wall was erected, and goes past a number of places where it still stands.

USING THE WALK

You can read the walk instructions directly from your smart phone. There are links in the text that lead to further information about particular points of interest.

If you don't want to read the walk instructions on your phone, you can click here to download a printable PDF version of this walk guide.

- Directions are shown in Black

- London Wall History Notes are shown in Red

- Incidental History notes (not Wall related) are shown in Blue

- Towards the end of the walk (Jewry Street) there is an indoor exhibition showing a section of the London Wall together with historical items found when the site was excavated. It is free, but they advise booking timed places online to guarantee entry. Click here to go to the "City Wall and Vine Street" website to book places.

The walk starts at the St Paul's tube station. At the top of the escalators, take the exit on the right (Exit 2), towards St Paul’s Cathedral. At the top of the steps, at street level, look left to see a stone bas-relief of a boy sitting on a basket. It’s on the wall of a coffee shop. Walk over to it.

The Panyer Boy

You are in Panyer Alley, thought by some to be named after “The Panyer”, an inn near here which burned down in the Great Fire of 1666. However, in the late 16th century, John Stow, an English historian, suggested that the alley got its name from a sign depicting a baker’s boy sitting on his bread basket. The bas-relief (or an earlier version of it) might have been what Stow was talking about. Called “The Panyer Boy”, there is much modern speculation as to what the bas-relief was first used for. It may have been a sign on the inn, or a sign on a bread shop (Bread Street, the centre of baking in medieval London, is the first turning down Cheapside from here). A Panyer (Pannier) is a traditional basket for carrying bread.Below the Panyer Boy is a dated panel. It seems unlikely that they were originally put together as they are now, as they differ in width and style. The panel reads: “When ye have sought the City Round. Yet still this is the highest ground. August 27th 1688”

Roman Londinium was built on two gravel hills, Ludgate Hill (where you are now) and Cornhill, now near the Bank of England. The hills were surrounded by the marshland and clay of the Thames flood plain. It was long thought that Ludgate Hill was the higher of the two. However, modern surveying has shown that in fact, Cornhill is higher by about 30 cm.

Walk towards St Paul’s cathedral down Panyer Alley. At the junction with the St Paul’s Churchyard path, turn right and walk around the Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cross

On your left, through the Cathedral railings, you can see St Paul's Cross. This is the latest incarnation of what was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit, dating from the 13th century. Paul’s Cross (an early spelling was "Powles Crosse") was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England. Many important statements on the political and religious changes during the Reformation were made public from here. For example, after the accession of Queen Mary (Tudor), Bishop Bourne announced here the religious changes that were planned. It was not well received, and a riot took place. A dagger was thrown at Bourne, fortunately missing him and sticking into one of the wooden side posts near him. Bourne was shaken by the rioting, and had to be moved to safety, withdrawing into St Paul's School which was near here.When you get to the front of the cathedral, cross over Ludgate Hill on the pedestrian crossing. Turn left and walk along, then turn right to Dean’s Court. At the end of Dean’s Court, turn right into Carter Lane.

Carter Lane

Carter Lane is a very old thoroughfare, probably dating from at least the 12th century, when it was then known as Shoemakers’ Row.

Its current name appeared at the beginning of the 13th century, when it was then divided into two parts, Great Carter Lane and Little Carter Lane.

The ‘Carters’ part of the name was probably used because it was a popular route used by goods carriers.

Wardrobe Place

On your left you will pass Wardrobe Place, a passageway leading to a small courtyard surrounded by Georgian houses, some with pretty fanlights above the doors. The houses are mostly offices, and the space has recently been used for outside eating and drinking.

It’s origin was a 14th-century house on this site, that was sold to King Edward III in 1359, and renamed the King’s Wardrobe. The building was used for storage of the ceremonial robes of the Monarch and the Royal Family, as well as those of ambassadors, ministers, and various other office-holders. The Royal Household accounts were also maintained here.

After a break during the English Civil War, when it was used to house orphans, the building continued to be used to house the royal wardrobe, until it was finally destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Continue along Carter Lane, then turn left into St Andrew’s Hill.

A short way down, turn right at the Cockpit pub into Ireland Yard.

Blackfriars Priory and the London Wall

At the intersection of St Andrews Hill and Ireland Yard, there was once a gatehouse above an entrance into the Blackfriars Priory. In 1613, William Shakespeare purchased the gatehouse. It’s thought that he bought it as an investment, as he also left London for Stratford-upon-Avon in 1613, and died there three years later.

The name Blackfriars refers to the black tunic worn by the Dominican Friars who ran the priory.

From 1276 onwards, a portion of the Roman city wall near here, that ran north to Ludgate and south to the Thames, was demolished. A new section of wall was then built that ran beside the Fleet River, and connected with the old Roman London Wall at Ludgate. A new priory was built in the area created by moving the wall, and the Blackfriars moved here from Holborn. Like other religious establishments, the priory was dissolved in 1538 as part of Henry VIII’s dissolution of monasteries, and sold off for secular use.

Continue walking along Ireland Yard and into Playhouse Yard.

Playhouse Yard

Playhouse Yard is so named as it was the site of The Blackfriars Theatre. This was an early indoor theatre, used in the winter from 1609 by The King’s Men, the players group William Shakespeare was part of. The Globe Theatre, being open air, was only used by the players group in the summer.

Walk straight on through Playhouse Yard, then turn left down Blackfriars Lane.

At the junction with Queen Victoria Street, turn right.

The south-west corner of the London Wall

Just on your right, you will pass the Black Friars Pub. This is approximately where the new section of the London Wall was built in the very early 14th century, in order to make space for the new Blackfriars Priory (mentioned above). The new wall went east and north from here. Land was reclaimed from the Thames using the wall (the Thames was shallower and wider then) giving extra space for the new Priory.

Walk on, then turn right into New Bridge Street and walk along it.

The London Wall along the River Fleet

New Bridge Street runs approximately along the path of the Fleet River, which ran south here as it flowed into the Thames. You can see in the landscape how the river flowed down here. New Bridge Street slopes down to the Thames from Holborn viaduct, Farringdon and beyond.

The Fleet still runs, but now in a pipe beneath the road. It emerges into the Thames under Blackfriars Bridge. The part of the London Wall that was rebuilt nearer to the Fleet, to make space for the Blackfriars Priory, ran along here on the right too.

Turn right into Pilgrim Street and walk up the steps towards St Paul’s.

The “new” 13th century London Wall which separated Blackfriars Priory from the Fleet River turned east here, and ran along where Pilgrim street is now. It went up to Ludgate, where it joined the original Roman Wall going north.

Continue up Pilgrim Street, then turn left into Pageantmaster’s Court.

A ‘Pageantmaster’ is someone who organises large celebratory events. There have been Pageant Masters in London for hundreds of years. The annual Lord Mayor’s Show today is organised by someone who holds the same title.

Pageantmaster’s Court ends at the junction with Ludgate Hill.

Ludgate

The Ludgate itself, on the Roman city wall, was approximately here, across the Ludgate Hill road.

Geoffry of Monmouth, in his book Historia Regum Britanniae (1136) said that Ludgate was named after an ancient British king called Lud. However, Lud is now thought to be a mythical figure, and that the name Ludgate derives from either "flood gate", "Fleet gate", or the Old English "hlid-geat", meaning a "postern" (a back gate).

Over the road and to the right, is the church of St Martin within Ludgate, indicating it was just inside the gate.

Cross over Ludgate Hill, have a look at St Martin within Ludgate, then walk back, and turn right into Old Bailey.

The Old Bailey runs parallel to the path of the London Wall. When walking up Old Bailey, the Wall would be on your right, with you just outside it.

The Old Bailey

The name of the Old Bailey road derives from the word "bailey," which is a Middle-English term for the outermost wall or court of a fortification. The law courts nearby, took their name from the street.

Walk up Old Bailey, past the Central Criminal Court on your right. Stop when you get to the junction with Newgate Street.

Newgate

This junction was the site of the Newgate, across what is now Newgate Street. Over the road to the left is St Sepulchre Without Newgate, indicating it was just outside the gates. It was one of the original Roman gates in the London Wall, and was originally a double-archway entrance into Londinium.

Cross over Newgate Street and continue in the same direction, past the Viaduct pub, into Giltspur Street.

Newgate is also famous for the prison that was built here, originally in part of the gate buildings. It was built in the 12th century by King Henry II, and remained in use up to 1902,.

Shortly, on the right, go under an arched entrance onto a footpath past St Bartholomew's Hospital.

This turning approximately follows the path of the London Wall, which also turned right at this point.

NOTE - If the gate to the Bart’s footpath is locked, return to Newgate Street and turn left. Continue along Newgate Street, then turn left into King Edward Street, and on the right is the gate to Postman's Park. If you do this, skip forward in these instructions to where you enter Postman’s Park.

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as 'Barts', was founded in 1123 by Rahere, who was an Anglo-Norman priest and monk and a favourite of King Henry I. It was refounded by King Henry VIII in 1546, who granted the hospital to the Corporation of London.

As you walk along the Bart's footpath, you are following the line of the London Wall.

On your right, from 1225 to 1538 would have been the Greyfriars Franciscan Priory. It was just inside the wall in the parish of St Nicholas in the Shambles. It was the second Franciscan religious house to be founded in the country and had a studium (a sort of university). It also had an extensive library of logical and theological texts, and in the early 14th century was an important intellectual centre.

At the end of the Bart's footpath, cross over King Edward Street and enter Postman's Park.

Postman's Park is so named as it is near the site of the former headquarters of the General Post Office (GPO). It was opened in 1880 on the site of the former burial ground of St Botolph's Aldersgate. It was later enlarged to incorporate the burial grounds of Christ Church Greyfriars and St Leonard, Foster Lane.

In 1900, George Frederic Watts' Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice was installed. It is a memorial to people who died saving the lives of others, consisting of ceramic memorial tablets housed on a long covered wall.

There is some archeological evidence that the London Wall followed a path under or very adjacent to the park.

At the other end of Postman's Park, you arrive at the point where St Martin's Le Grand becomes Aldersgate Street.

Cross over Aldersgate Street and turn right.

On the Lord Raglan pub is a plaque marking the place that the Aldersgate straddled the road.

Just after the pub, turn left into Gresham Street.

Aldersgate

Aldersgate was not an original Roman Gate, from when the Wall was built at the start of the 3rd century. It was added later in the British Roman period. The name used now to describe it was probably acquired in the late Saxon period.

The old Aldersgate was demolished and rebuilt in 1617. It was later damaged in the Great Fire of 1666 and later repaired. It remained until 1761, when it was demolished to aid the flow of traffic.

Turn left into Gresham Street and continue along it.

Sir Thomas Gresham

Gresham Street is named after Sir Thomas Gresham, who was born in London in 1519, the son of a Lord Mayor. He developed great financial skills, and built a fortune.

Sir Thomas Gresham, portrait c.1554 by Anthonis Mor - Public Domain

Under Queen Elizabeth I, Gresham acted as Ambassador Plenipotentiary (an ambassador able to make independent actions) to the Court of Duchess Margaret of Parma. He was appointed a Knight Bachelor in 1559 prior to his permanent departure in 1567, caused by the Dutch revolt. Sir Thomas spent the rest of his life in London, successfully working as a government financial agent and as a merchant, making him extremely wealthy.

Gresham made a proposal to the City of London, to build, at his own expense, what became the Royal Exchange. A stipulation was that the Corporation provided a suitable location for it. This was to be based on the Antwerp Bourse, a commodity exchange, which Gresham had some experience of.

Gresham died suddenly on 21 November 1579. It was thought the cause of death was apoplexy (probably a stroke). He was buried at St Helen's Church, Bishopsgate, near to his home.

In his will, Thomas Gresham left funds to institute a college. The college was to have seven professors who would read lectures in astronomy, geometry, physic, law, divinity, rhetoric and music. In 1597, this became Gresham College, the first institution of higher learning in London. Gresham college still exists, and free lectures are still given to the public.

Turn left into Noble Street, where we will see the first bit of visible London Wall in the walk.

The first sight of the London Wall

Along Noble Street, is a raised platform from where you can view this long stretch of city wall remains. This was originally part of a fort that was built before the London Wall, and then incorporated into it later.

The wall here dates from the second to the nineteenth century. It was lost, but revealed again in 1940, after clearing German bomb damage in the area.

The original Roman wall would originally have been about 5 metres. You can see the Roman section at the base of some of the remains, by the horizontal layers of red tiles.

Access to the top of the wall would have been via a set of sentry towers, the remains of one can still be seen towards the south side of the remains. This sentry tower also marked the south west corner of the old Roman fort.

Medieval tiling and stonework can be seen at the northern end of the remains. In places where the medieval wall hasn’t survived, a patchwork of 19th century brickwork can be seen.

There are information panels in front of the wall here that are useful for putting the London Fort and Wall into context.

St Olave’s, Silver Street and William Shakespeare

On the right, at the north end of Noble Street, is the site of St Olave’s Churchyard. The church itself was burned down in the Great Fire of 1666, and never rebuilt.

On the right, at the north end of Noble Street, is the site of St Olave’s Churchyard. The church itself was burned down in the Great Fire of 1666, and never rebuilt.

The area which is now pavement, between the Churchyard and what is now the road called London Wall, was called Silver Street. William Shakespeare lodged here in the house of Christopher Mountjoy, a Hugenot maker of "Tires" (ladies head adornments), in the very early 17th century. It is one of the few places that Shakespeare lived in London, that we know the actual address of. This is because records still exist of a court case, involving Mountjoy, to which Shakespeare gave a witness statement. Silver Street disappeared due to redevelopment, which was needed after the extensive damage to the area, caused by bombing in the Second World War.

Cross over the London Wall road, there is a pedestrian crossing a few metres down towards the London Museum. Walk back to opposite St Olaves Churchyard.

There is a curved ramp here that leads down towards an underground car park. Walk down the pavement on the ramp, and before you get to the car park, take the earth path on the right, next to the Bastion, into the garden of the Barber Surgeons Hall.

There are several Bastions here (projecting towers to aid defence). These were part of the Cripplegate Fort, to which the London Wall was subsequently added. The Fort, originally Roman, had the Bastions added in the Medieval period. Walk right to the end, where there is a pond. Beyond the pond is the Barbican estate. The name Barbican comes from an Old English word meaning "an outer fortification of a city or castle".

The Bastions in the Barber Surgeons Hall gardens. Made using Google Earth

The Fort on the London Wall

Before the London Wall was built around 200 CE, a London Fort had been built between 110 -120 CE. This is the area that you are walking around now. It was a square structure, roughly 200 metres down each side. When the Roman Wall was built around the settlement to the south east, the fort was incorporated into it. The Roman Fort is the square structure that the wall was built on to.

By the Medieval period, the south and east wall of the Fort had been removed. Bastions were added to the remaining walls, and it’s these that we can see in the Barber Surgeons garden. A bastion is a structure that projects outward from the curtain wall of a fortification. They are often positioned at the corners of a fort to protect both the wall and any adjacent bastions.Return on the earth path the way you came. When you get to the entrance to the underground car park, you can enter and visit another piece of the London Wall in a parking bay! On entering the car park, turn left and walk (quite a way) along to bay 54.

The London Wall in a Car Park

This part of the Roman Fort section of the London Wall was uncovered in 1957 as part of road developments. Some medieval sections of wall around it were demolished, but this section was retained, as it was thought a very good example of Roman origin wall.

There had been a Saxon church on this site in the 11th century but by 1090 it had been replaced by a Norman one. In 1394 it was rebuilt in the perpendicular gothic style. The stone tower was added in 1682.

There had been a Saxon church on this site in the 11th century but by 1090 it had been replaced by a Norman one. In 1394 it was rebuilt in the perpendicular gothic style. The stone tower was added in 1682. Cripplegate

CripplegateThe origins of the Cripplegate's name are not clear. One theory, based on the spelling in some old documents as "Crepelgate", was that the name is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word crepel, meaning a covered or underground passageway.

Wikimedia Commons Image

Another theory is that it was so named because it may have had disabled people gathering there to beg. The fact that as St Giles without Cripplegate is the local church, and Saint Giles is the patron saint of cripples and lepers, may give weight to this theory.

Walk down St Alphage Garden. On the left are more remains of the London Wall.

Salters’ Garden

On the left, at the end of St Alphage Garden, is the entrance to another interesting garden, on the other side of the wall. This is called Salters’ Garden and is owned by the Salters’ Company, one of the 12 Livery Companies (Guilds) of the City of London. Their Hall is the white building next to the garden. If the garden is open, it is well worth a visit, as the garden is lower, so that you can see more of the deeper, older parts in this section of the London Wall.

Tower of Elsyng Spital

On your right, you will pass the ruined tower of St. Alphege's Church on London Wall, which is known as Elsyng Spital. It was part of the medieval hospital of Elsyng Spital.

The name comes from William Elsyng, who was a London merchant. He founded the hospital in 1330 to provide help for London's destitute.

Elsyng's hospital remained part of an Augustinian priory until it was closed in 1536.

Turn right at the end of St Alphage Garden, then left on to London Wall. Continue along London Wall to Moorgate. Cross over Moorgate.

Moorgate

Moorgate is a medieval gate. Originally a Postern (a back, or secondary gate) being made a full size gate in 1415. It’s name comes from the fact that the land outside the gate was marshy. The reason it was like this was that the Walbrook (Wall brook!) flowed south to the Thames here, and the Romans built the wall right across it. Because a ditch was built around the wall, this became filled with water from the Walbrook. When the Moorgate was built, the Walbrook was channeled, and diverted underground towards the Thames.

Walk on, along London Wall.

Just before it turns into Wormwood Street, you will pass All Hallows’ On The Wall on the left. The name of this church refers to where it is, next to and within the London Wall.

When you get to Bishopsgate, turn left and walk up it a few metres.

Bishopsgate

Bishopsgate was first built in the Roman era. The road passing through the gate is now called Bishopsgate, but was originally called Ermine Street, a Roman Road from London to Lincoln and York. The name Ermine Street is a corruption of "Earninga Straete", named after a tribe called the Earningas, who lived in the Cambridgeshire / Hertfordshire area which the road passed through.

The gate is thought to be to be named after Earconwald, a 7th century Bishop of London (and of the East Saxons) who, it’s said, paid for the gate to be rebuilt.

Cross over Bishopsgate and follow the line of the London Wall, down Camomile Street. Don’t turn left into Outwich Street, but cross over it and bear slightly right to stay on Camomile Street. Camomile Street becomes Bevis Marks, and then Duke’s Place. Where Duke’s Place starts to turn left, walk straight ahead into Aldgate Square.

Walk past Aldgate School on the right to arrive at the Aldgate information panel.

Aldgate

There are no physical remains of Aldgate visible here now. A new information panel shows pictures of local archeological finds and other historical information. Aldgate was just here across what is now Aldgate High Street, a blue plaque on Boots the chemist shows the approximate place.

When the Aldgate was first built, what went through it was “The Great Road”, the Roman Road from London to Colchester.

St Botolph Without Aldgate is on the other side of Aldgate Square, showing that it was just outside the London Wall.

Theories about the origin of the name Aldgate include that it was derived from: Æst geat meaning east gate, Aeld Gate meaning an old gate, Aelgate meaning a public gate, and Ale Gate because there was an inn nearby.

Geoffrey Chaucer, the author of the Canterbury Tales, lived above the city gate of Aldgate from 1374. Chaucer had a post as 'Controller of Customs', one of the perks of which was free accomodation here.

After reading the information on the panel, cross over Aldgate High Street at the pedestrian crossing, and then walk down Jewry Street, passing the Aldgate blue plaque on the wall of Boots on the left .

Jewry Street follows the path of the London Wall, which is to your left (you are now inside the wall).

Immediately after passing India Street, on the left there is a passage through the building. On the right of the passage is a doorway into the "City Wall on Vine Street" exhibition.

You can view a section of the London Wall that was a Bastion (a tower) at close quarters here. There is also an exhibition of historical artefacts, found when the area was excavated before the current building was erected. The items were lost or dumped on the site through the years.

It's free to enter, but you should book a place online first to ensure entry.

You can book free entry places by clicking here to go to the City Wall and Vine Street website.

On leaving the exhibition, turn right and continue walking under the building. Turn right into Vine Street.

Vine Street

You can look at a stretch of the wall here through the plate glass window of 'Urbanest' (used for student accommodation). The wall is below the current ground level. This is because over the years, the cycle of building / demolishing / rebuilding / etc. has raised the ground level of London in some of it's areas Walk through the car park towards the Wall.

Walk through the car park towards the Wall. When you have looked at the wall here, return through the gap in the wall to the car park, and out to the street. Turn right and continue along.

Pass a crescent of houses on the right. The original Georgian houses on this site were destroyed in World War II, the houses here now are copies of the originals, rebuilt in the 1960's.

Pass under a building, towards the Tower of London. Immediately turn right and walk towards one of the tallest remains of the London Wall.

Walk up to Tower Hill Roman Wall, then go past it and turn left down the steps to get nearer to it.

Tower Hill Roman Wall

The Tower Hill Roman Wall is one of the highest remaining parts of the old London Wall. The Roman sections of the wall are clearly visible in the lower four metres. The upper stonework, taking the wall up to about ten metres, is Medieval. The wall is made of Kentish Ragstone, thought to have been bought from Maidstone on barges. The Roman section has horizontal bands of red tiles, which it’s thought were used to strengthen and stabilise.

When first built, the Roman Wall here would have stood at around 6 metres high.

On the outer side of the wall there would have been a deep ditch, providing additional defensive measures. This ditch would have increased the height of the wall from the exterior, and also have made the ground wet and boggy.

There is a statue of Roman Emperor Trajan standing in front of the wall here.

The statue of Trajan was installed in 1980. It was left as a bequest by the vicar of All Hallows-by-the-Tower, the Reverend P.B.Clayton. The sculptor is unknown.

The statue is a cast, made from a late first century statue found in Minturno, Italy. It is now on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. The upper part of the head has been restored.

Trajan was a Roman emperor who ruled from A.D. 98 until his death in A.D. 117. He never visited Britain.

From the Trajan Statue, continue down the steps, then through a tunnel under the road to arrive at the Medieval Postern Gate, which has great views of the Tower of London.

The Medieval Postern Gate

Around 1270, part of the London Wall was demolished, in order for the Tower of London moat to be excavated. The Postern Gate (postern means a side or back entrance) was built between 1297 and 1308 at the edge of the moat. Its purpose was to be a defensible terminus to the city wall, and also a minor pedestrian gateway. It seems likely that the Gate had inadequate foundations, as it subsided by about 3 metres in around 1440. In spite of this, the Gate remained standing, and with some rebuilding, was used until at least the early 17th century.

WALK END

The London Wall walk ends here.

If you fancy a drink or something to eat, about 130 metres away to the west, are a couple of decent pubs, Traitors Gate and the Liberty Bounds. There is also a monument marking the site of the Tower Hill Scaffold, which you may wish to explore, which is near the pubs.

Return through the tunnel under the Tower Hill road, and back up the steps to the top. On your left is Tower Hill Tube Station (District and Circle Lines), and if you turn right you will get to Tower Gateway DLR Station.

If you retrace your steps back to Bishopsgate, and turn right, Liverpool Street Rail and Underground Stations are about 15 minutes away.

Send us your feedback!

Link to feedback form

Let us know if you enjoyed the walk and if you have any other feedback we could use to improve it.

Russell & Paul